As we shift gradually into spring, the days are getting longer, which is pleasant. Unfortunately the weather has been erratic at best, with constant rain showers throughout the day. Two weeks ago on Thursday (March 31st) I recall experiencing the worst weather I’ve ever seen since coming to Paris: the rain just wouldn’t let up, and to make things worse Thursday was also the day when public transport workers and students simultaneously went on strike against proposed changes to labour laws. Only 3 out of 4 trains on the Paris metro were running, while only 1 out of 2 trains on the RER (Paris’ suburban train line) were in service.

For weeks now, trouble has been brewing on the political front in France. The El Khomri law (“la loi El Khomri”), proposed by the French Labour Minister Myriam El Khomri, has attracted widespread protest and condemnation, mostly from labour unions and students who feel threatened and directly affected by any changes to workplace law. The reforms to labour laws would allow companies to extend the maximum length of a work day from ten to twelve hours if necessary, meaning that some workers would be required to work up to 60 hours a week. In addition, the El Khomri law would make it easier for companies to retrench workers on economic grounds should companies run into financial difficulties, putting vulnerable workers in an even greater position of risk. Since an initial draft of the law was made public through media channels on 17 February, over 200 000 people have taken to the streets to protest these possible changes, first on the 9th of March (224 000 protestors) and subsequently on the 31st of March, which had the greatest turnout of protestors thus far at 390 000 people in 250 cities, according to this live feed from Le Figaro. These protests have not been confined to the capital but have in fact spread from Paris to other cities in France, notably Toulouse, Lyon and Marseille. Demonstrations on 31st March also affected public transport: only 3 out of the 4 trains on the Paris Metro were running, and only 1 out of 2 trains on the RER (the suburban line) were in service.

Although the landmark protest of 31 March took place more than two weeks ago, protests and general dissatisfaction with the laws show no signs of abating. Having gathered significant momentum and support, particularly among sixth-form and university students, the protests have evolved into an even greater social movement, now termed Nuit Debout (“Up All Night”). Though changes to labour laws were once the focus of these protests, since March 31, which is when the Nuit Debout movement officially came to life with a night-time sit in at Place de la République, a symbolic spot in Paris that has previously seen protests after the Charlie Hebdo attacks last January and the Paris attacks in November), the Nuit Debout gatherings are now being used by protestors to vocalise their dissatisfaction with a wide range of issues, including the dismal state of the economy and elitism within the government. In many ways, these social movements are reminiscent of Occupy and Spain’s Indignados anti-austerity movement as they involve a large group of disenfranchised citizens, many of them youths, railing against the establishment as well as what they see as the Socialist government’s failure to protect society’s marginalised.

From a geographical perspective, the way in which the key issues driving the protests have evolved gradually has been interesting to note – although the movement initially began with protests against the reforms in labour law, it now symbolises a “national crisis”, according to the French political scientist Claire Demesmay in an interview with Deutsche Welle, that conflates together a whole host of societal problems. Initial unhappiness with the labour reforms stems from the fact that “many […] do not want to work under worse conditions”, with “the great dream [remaining] the open-ended employment contract”, but this has evolved into a socio-economic as well as an identity crisis. Demesmay states that some French citizens “no longer understand France’s place in this world and the world of the future. And then the reactions are denial and disassociation”, which take the forms of not only criticism of the elite, but also “xenophobia” and “Euroskepticism”. The Guardian’s article on the Nuit Debout protests references some of these sentiments – protestors interviewed stated that the Socialist government has failed to deliver on its promises to fix the broken economic system and improve employment opportunities, and that “the labour law was the final straw” after “the stage of emergency, the new surveillance laws, the changes to the justice system and the security crackdown”.

Drawing on geographical debates, the protests can be seen as the exercise of citizens’ right to the city and their general dissatisfaction and insecurity in a world increasingly governed by fluxes and rootlessness. Nuit Debout can be seen as an example of the “backlash against neoliberal globalisation” that proceeds from “the problems and contradictions linked to the power of capital” as well as “the encroachment of political, social, and ecological mono-cultures associated with the supremacy of corporate rule” (Gill 2000: 133), and this simmering unhappiness has played out in the form of long-drawn social protests in “divided and conflict-prone urban areas” (Harvey 2008, The Right to the City) within France. As Stephen Gill writes in his landmark article Towards a Postmodern Prince? (that was covered heavily in our Year 1 Global Geographies class), social movements after the millennium increasingly stem from the political and socio-economic contradictions of neoliberal globalisation which have left citizens in diverse contexts feeling dispossessed and disenfranchised. “Disciplinary neoliberalism proceeds with an intensification of discipline on labour and a rising rate of exploitation” (Gill 2000: 134), and in this context El Khomri’s revision of labour laws, designed to increase the competitiveness of French corporations and turbo-charge the French economy, are viewed with suspicion by the general populace, who feel that the government has sidelined workers’ needs in favour of aiding big corporations.

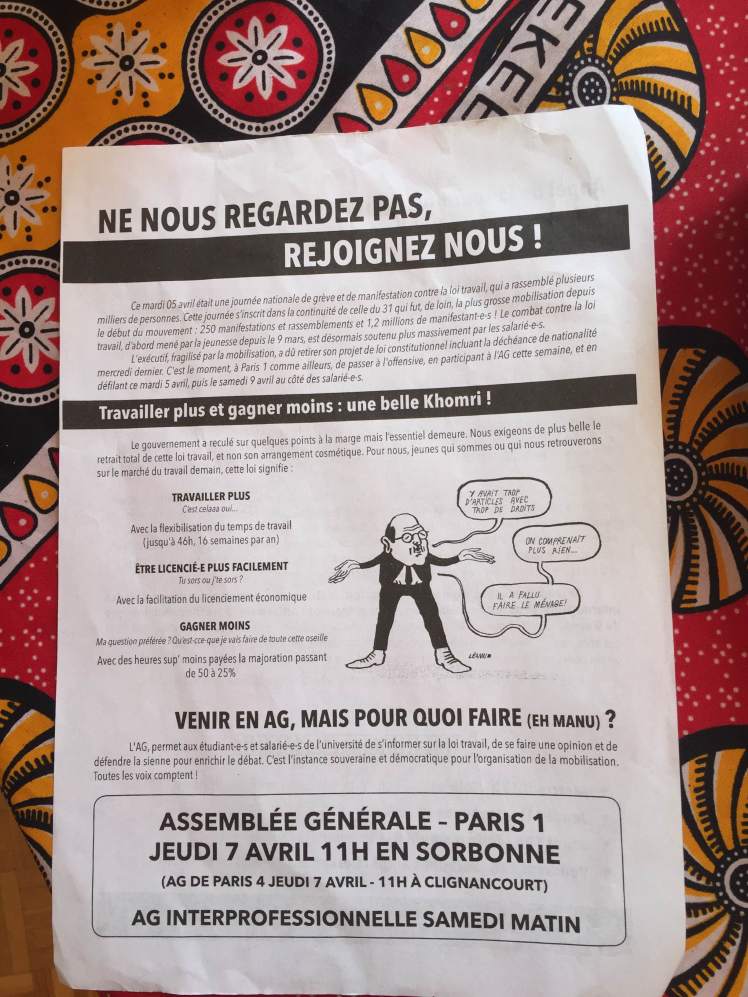

Likewise, it has been interesting to see just how quickly the protests in France have gained momentum and drawn a large crowd of people to a similar cause – the huge turnout of nearly 400 000 protestors on the nationwide protests of March 31st can be attributed to activists spreading the word among their immediate social networks, especially in school. The French media have focused on the youthful aspect of the protests, stating that a fifth of the protestors who took part in the demonstrations on March 31st were high school and university students. Even around the Sorbonne, flyers and posters encouraging students to join the activist movement are conspicuously put up (see picture below), making high schools and universities into “social movement spaces” (Massey in Nicholls 2009) as students have the opportunity to connect to one another, spreading the word and strengthening the social capital among these actors. At the same time, widespread use of social media such as Twitter and Facebook to organise public meetings and events “facilitate new connections with distant allies [and] also help sustain newly-established relations” (Nicholls 2009: 86). What has been fascinating for me personally is also seeing how diverse actors, ranging from public transport workers to students, have all rallied together for a common cause – indeed the Guardian article’s interviews with various protestors show that they come from all ages, backgrounds and walks of life, which is in line with what Nicholls (2009: 86) writes: “broadening the geographical and social base of a political insurgency necessarily introduces a wide range of diverse actors into the mix (della Porta and Tarrow 2005; Tarrow and McAdam 2005)”.

Already there have been signs that the government is giving in to the demands of the protestors, stating that there will be amendments after a parliamentary debate, although Hollande is adamant that it will not be scrapped. As long as the protestors view these laws as an encroachment on their personal liberties and welfare however, I am certain that the Nuit Debout movement will continue to persist.

Bibliography:

20 Minutes (2016). La loi El Khomri «ne sera pas retirée», assure Hollande [Online]. Paris: 20 Minutes. Available at: http://www.20minutes.fr/societe/1827083-20160415-loi-el-khomri-retiree-assure-hollande [Accessed: 19 April 2016].

Chrisafis, A. (2016). Nuit debout protestors occupy French cities in revolutionary call for change [Online]. London: The Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/apr/08/nuit-debout-protesters-occupy-french-cities-in-a-revolutionary-call-for-change?CMP=fb_gu [Accessed: 19 April 2016].

Gill, S. (2000). “Toward a Postmodern Prince? The Battle in Seattle as a Moment in the New Politics of Globalisation”, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 29, 1, pp. 131 – 140.

Harvey, D. (2008). “The Right to the City”, New Left Review, 53, September – October 2008.

Hasselbach, C. (2016). Nuit debout: middle-class protests in France [Online]. Berlin: Deutsche Welle. Available at: http://www.dw.com/en/nuit-debout-middle-class-protests-in-france/a-19194271 [Accessed: 19 April 2016].

Le Figaro (2016). EN DIRECT – Loi travail: mobilisation plus forte que le 9 mars selon les syndicats [Online]. Paris : Le Figaro. Available at: http://www.lefigaro.fr/economie/2016/03/31/20003-20160331LIVWWW00015-en-direct-greve-RATP-SNCF-metro-loi-El-Khomri-travail-manifestations.php [Accessed: 19 April 2016]

Nicholls, W. (2009). “Place, networks, space: theorising the geographies of social movements”, Transactions of the British Institute of Geographers, 34, pp. 78 – 93.